Table of Contents

Introduction: A Deep Dive into Georgia’s School Lunch Crisis (Part 1)

“Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” This famous quote by Anthelme Brillat-Savarin underscores the intimate connection between our diet and our health. For children, this connection is even more profound, as their growing bodies and developing brains rely heavily on the quality of their nutrition.

(Please Check out Part 2 where we look at school lunches from Europe and Asia and Part 3 where we discuss solutions to the problem.)

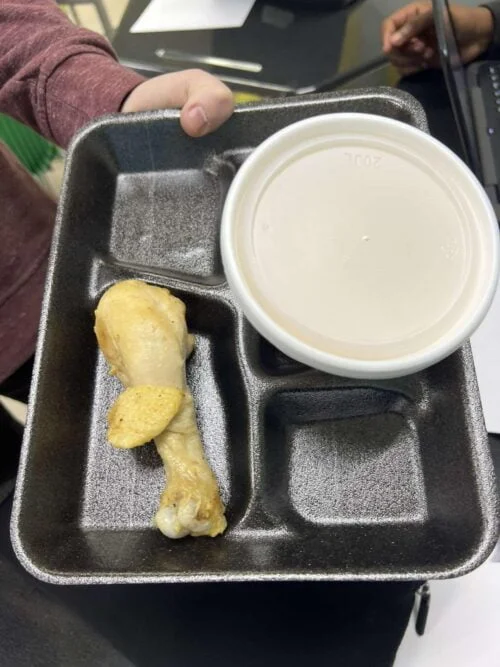

As a mother of two children in public schools in Cobb County, Georgia, I have firsthand experience of the quality of meals our children are served. The truth is, the meals in Cobb County aren’t much better than those in Bibb County, a fact that became glaringly evident in a recent viral Facebook post from Bibb County. This post, shared by a concerned parent, showcased a meal consisting of a barely-cooked chicken leg and a cup of canned peaches, serving as a stark representation of the state of school lunches in our state.

This image was not an anomaly but a symptom of a widespread issue. Other parents and students shared similar images and stories, painting a grim picture of school lunches across the district and beyond. This three-part series aims to delve into this crisis, exploring the state of school lunches in Georgia, the wider implications for our children’s health, and the systemic changes necessary to rectify this situation.

In this first part, we will examine the current state of school lunches in Georgia, the health implications of these meals, and the need for immediate intervention. With firsthand experiences, photos, and data, we will lay bare the unpalatable truths of Georgia’s school lunch crisis.

The Current State of School Lunches in Georgia

When a concerned parent in Bibb County, Georgia, shared a photograph of a school lunch consisting of an undercooked chicken leg and a cup of canned peaches, the image quickly went viral on Facebook. This meager meal hardly fits the criteria of a nourishing, balanced diet that we expect to be served in our schools. According to the USDA guidelines, a proper school lunch should include fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and milk. Regrettably, the lunches depicted in these posts fall disappointingly short of these standards.

Data paints a concerning picture of the state of school lunches in Georgia. A 2021 study conducted by the Georgia Department of Education found a significant variation in school meal quality across the state’s 181 school districts. For example, Fulton County Schools, one of the largest school districts in Georgia, introduced a farm-to-school initiative aiming to provide students with fresh, locally grown produce. But even in these districts, striking the right balance between budget constraints and nutritional quality is a significant challenge.

On the other end of the spectrum, school districts in lower-income areas often struggle to meet even the minimum nutritional standards, due to budget restrictions. These districts tend to rely heavily on pre-packaged, processed foods, which are cheaper and have a longer shelf life. The stark contrast between school districts underscores the problem of unequal access to nutritious meals for students across the state.

The comments on the viral Facebook post shed further light on the state of affairs in Bibb County. One day, the lunch was a small frozen pizza and an apple; on another, it was a few nachos with some meat sauce; and a senior graduate breakfast comprised of a small waffle with a handful of blueberries. Separate photos showed a moldy orange and a soggy, unappetizing piece of bread, further demonstrating the poor food quality being served.

What’s more troubling, according to some commenters, is that students in the Bibb County School District are not allowed to bring their own lunches. This policy makes these subpar meals their primary source of nutrition during school hours. Additionally, the meals are consumed in the classroom, which raises concerns about sanitation and deprives teachers of a much-needed break during the day.

The parent who ignited this investigation didn’t mince words in the viral Facebook post: “I allowed my child to sign out early since this is what was offered for lunch! 1 chicken leg and a bowl of peaches …. No parfait left no cheese sticks as if that constitutes a meal in my opinion… I mean I’d rather pay than see this crap served.” The post resonated with others, one of whom commented, “Ewww I swear, when I first started reading this I thought you were talking about Bibb county Jail… It wasn’t until I read the word “school” that I realized this is school food and not jail food! Disgusting.”

The Health Implications

The school lunch debacle has far-reaching implications beyond the school grounds. These inadequate meals present grave health risks for the children consuming them. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) emphasizes the importance of a balanced diet in promoting the health and well-being of children. This includes preventing childhood obesity and promoting healthy eating habits that children can carry into adulthood.

The lunches served in Bibb County, however, do not meet these standards. An undercooked chicken leg and a cup of canned peaches, a few nachos with some meat sauce, or a small waffle with a handful of blueberries: these meals do not provide the necessary nutrients for growing children. They lack in essential elements like fiber, vitamins, and minerals, and are often high in sugar and unhealthy fats.

It’s well-documented that a lack of proper nutrition can hinder a child’s cognitive development and learning capacity. According to a 2018 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, children who consume low-nutrient, high-calorie diets are more likely to perform poorly in school. They often have difficulty concentrating, exhibit behavioral problems, and are more likely to miss school due to illness.

Over time, consistently consuming these nutrient-poor meals can also lead to chronic health issues like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that childhood obesity rates in Georgia are above the national average, with 18.4% of children aged 10-17 classified as obese. Poor nutritional habits established during childhood often persist into adulthood, making early intervention crucial.

The Time Constraint

School lunches in Georgia, and in many districts across the United States, face another significant issue beyond food quality – the time constraint. According to comments on the viral Facebook post, students in Bibb County are not only confined to their classrooms for breakfast and lunch but are also given a minimal amount of time to eat their meals.

This rushed lunch model not only raises concerns about sanitation in classrooms but also means that teachers have to monitor students during meal times, taking away an essential time to catch their breath and collect their thoughts without kids for a few moments. Additionally, this approach deprives students of the opportunity to socialize, relax, and recharge, which are equally important aspects of a school lunch period.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that students should have at least 20 minutes for lunch after they have received their meal. However, in many schools in the United States, including Bibb County, the reality is different. Students often have less time, and this period includes queuing, receiving their meals, finding a spot, and settling down to eat.

The implications of this rushed schedule are two-fold. Firstly, students may consume their food too quickly, leading to overeating. Rapid eating doesn’t allow the body time to register feelings of fullness, which can lead to excessive calorie intake and potential weight gain. On the other hand, if students find the meals unappetizing and don’t have enough time to eat, they may skip meals entirely. This can leave them hungry, lacking energy, and unable to concentrate during afternoon classes.

When compared to lunchtimes in other countries, the differences are stark. In France, for example, lunchtime can last up to two hours, giving students ample time to eat a multi-course meal. In Japan, students often have a role in serving meals and cleaning up, making the lunch period a learning experience in cooperation and responsibility. These longer lunch periods also teach students to value mealtime, appreciate their food, and develop good eating habits.

The rushed, constrained meal periods in Bibb County and other similar districts represent a missed opportunity. They fail to utilize the lunch period as a time for students to learn about healthy eating habits, enjoy their food, and develop social skills – lessons that are as crucial as any academic subject.

The Profit Factor

While the school lunch issue is multi-faceted, one aspect that is often overlooked is the role of profit in determining what gets served in school cafeterias. In many school districts across the country, including Bibb County, vending machines and school stores selling unhealthy snacks and beverages are common sights.

These outlets serve a dual purpose – they provide an alternative for students dissatisfied with the school-provided lunch, and they also generate revenue for schools. However, this financial gain comes at a cost. Schools may inadvertently be encouraging students to opt for unhealthy, processed food from vending machines and school stores over the less appealing, yet supposedly more nutritious, school lunches.

The prevalence of these alternative food sources can further exacerbate the poor nutritional intake of students. Products available in vending machines and school stores are often high in sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats. Regular consumption of such food can contribute to obesity, diabetes, and other health problems.

The revenue generated from these sources can be significant, creating a potential conflict of interest. Schools may be reluctant to improve the quality of school lunches if it means a reduction in sales from vending machines and school stores. This cycle perpetuates a system where student health may be sacrificed for financial reasons.

This is not to say that all vending machines and school stores are inherently bad. Some schools have successfully implemented policies to offer healthier options in these outlets, but such initiatives are not yet widespread.

The Bigger Picture

The crisis of school lunches extends far beyond the borders of Bibb County, or even Georgia. This issue is a nationwide concern, with considerable variation in the quality of school lunches from state to state.

For instance, states like California and New York have made notable strides in improving the quality of their school lunches, introducing farm-to-school programs, and implementing strict nutritional standards. However, many other states lag behind, often due to budget constraints or lack of emphasis on nutrition education.

When we look beyond the US, the differences become even starker. Countries like Japan, France, and Finland have taken school lunches to a whole new level. In Japan, school lunches are freshly prepared, nutritionally balanced, and serve as a learning experience for students. Children often serve their classmates, clean up after themselves, and learn about the nutritional value of the food they consume. Similarly, in France and Finland, school meals are seen as an integral part of education, with students given ample time to eat and enjoy their food.

The disparity between these countries and the US is significant and provides an impetus for change. The question that arises is: why can’t we adopt similar practices in our schools? It’s not just about the food, but the entire ethos surrounding meal times in schools. This topic will be explored in greater detail in the next part of the series.

Call to Action

The state of school lunches in Bibb County and across Georgia is a wake-up call. We need to stop treating the symptoms and start addressing the root causes of this issue. It’s not enough to simply demand better food. We need systemic changes that prioritize children’s health and nutrition over profits and convenience.

Parents, educators, and lawmakers all have roles to play. We need to hold our schools and districts accountable, lobby for better funding, and advocate for healthier options in school cafeterias, vending machines, and school stores. It’s time to make school lunches a matter of public interest and policy, rather than a footnote in the education system.

Parents, educators, and lawmakers all have roles to play. We need to hold our schools and districts accountable, lobby for better funding, and advocate for healthier options in school cafeterias, vending machines, and school stores. It’s time to make school lunches a matter of public interest and policy, rather than a footnote in the education system.

As Margaret Mead once said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” Let’s be that group for our children.

Conclusion

The viral Facebook post from Bibb County was a stark reminder of the unsatisfactory state of school lunches in Georgia. However, this issue is not confined to one county or one state. It’s a nationwide problem that requires collective action and systemic change. As we delve deeper into this issue in the next part of the series, we’ll explore the specific health consequences of poor nutrition in childhood, and potential solutions to this crisis. It’s time to ensure that every child, in every school, has access to a nutritious, appealing lunch. Because good nutrition is not a privilege – it’s a right.