The Science of Synesthesia and How It Affects Perception

Introduction

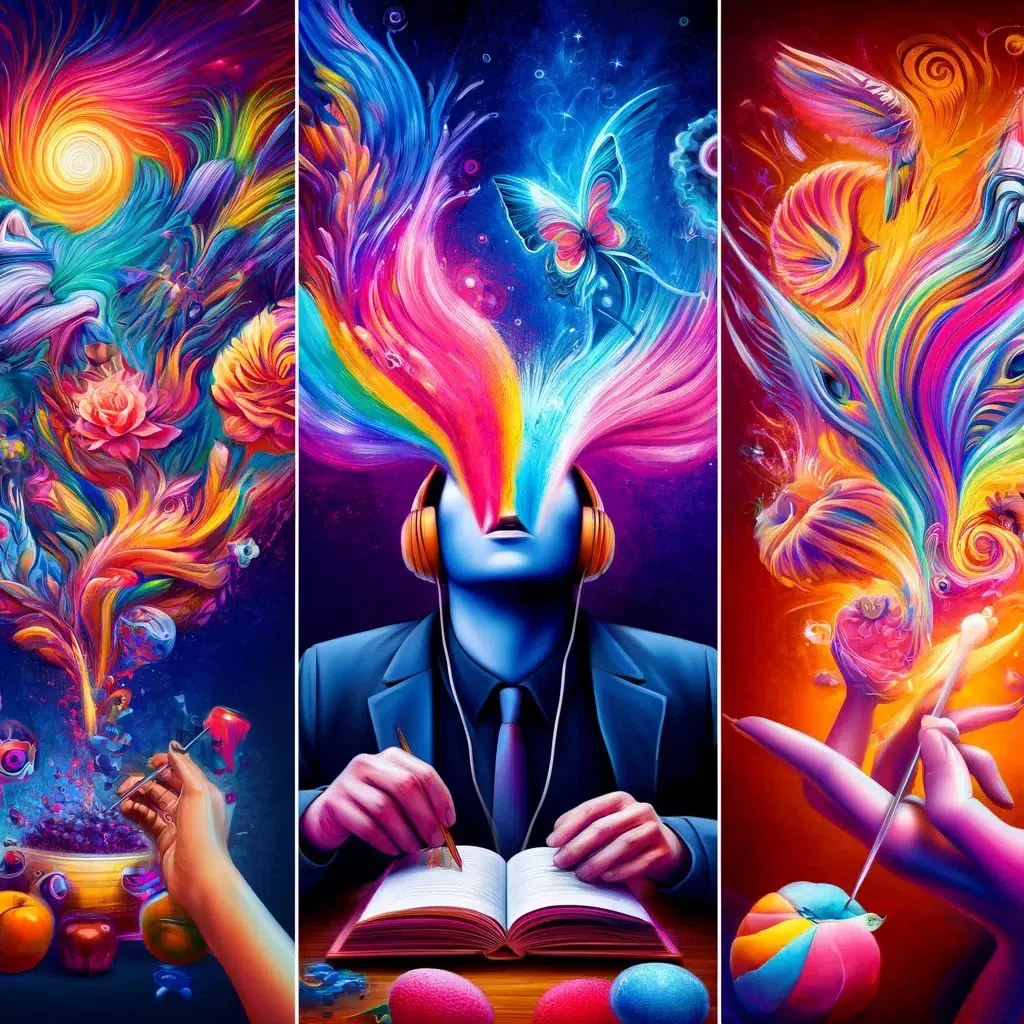

Synesthesia is a fascinating neurological phenomenon where the stimulation of one sensory pathway leads to involuntary experiences in another. For instance, individuals with synesthesia might see colors when they hear music or taste flavors when they read words. This unique blending of the senses challenges our traditional understanding of perception and provides intriguing insights into the brain’s functioning and memory. This article delves into the science behind synesthesia, its various forms, and its impact on those who experience it.

Synesthesia is a fascinating neurological phenomenon where the stimulation of one sensory pathway leads to involuntary experiences in another. For instance, individuals with synesthesia might see colors when they hear music or taste flavors when they read words. This unique blending of the senses challenges our traditional understanding of perception and provides intriguing insights into the brain’s functioning and memory. This article delves into the science behind synesthesia, its various forms, and its impact on those who experience it.

Understanding Synesthesia

Synesthesia, derived from the Greek words “syn” (together) and “aisthesis” (perception), literally means “joined perception.” It’s estimated that about 4% of the population experiences some form of synesthesia, although the actual number may be higher due to underreporting (Simner & Hubbard, 2013). Synesthesia is often discovered in childhood and tends to run in families, suggesting a genetic component (Ward, 2013).

Types of Synesthesia

There are over 60 known types of synesthesia, but the most common include:

- Grapheme-Color Synesthesia: Individuals see specific colors associated with letters or numbers.

- Chromesthesia: Sounds, such as music or voices, trigger the perception of colors.

- Lexical-Gustatory Synesthesia: Certain words evoke specific tastes.

- Number-Form Synesthesia: Numbers are perceived as mental maps or spatial arrangements.

- Mirror-Touch Synesthesia: Feeling a touch on one’s own body when seeing someone else being touched.

Each type offers a unique window into how the brain processes sensory information.

The Neurological Basis of Synesthesia

Research into synesthesia has revealed that it is linked to increased connectivity between sensory regions of the brain. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies show that synesthetes have heightened neural activity in areas typically associated with different senses. For example, in grapheme-color synesthesia, the visual cortex responsible for color processing is activated when the person sees numbers or letters (Hubbard & Ramachandran, 2005).

Research into synesthesia has revealed that it is linked to increased connectivity between sensory regions of the brain. Functional MRI (fMRI) studies show that synesthetes have heightened neural activity in areas typically associated with different senses. For example, in grapheme-color synesthesia, the visual cortex responsible for color processing is activated when the person sees numbers or letters (Hubbard & Ramachandran, 2005).

One leading theory suggests that synesthesia results from a “cross-wiring” in the brain, where neurons in one sensory area form connections with neurons in another. This cross-activation could be due to genetic differences, developmental anomalies, or a combination of both (Cytowic & Eagleman, 2009). According to a study published in Nature Communications in 2015, synesthetes showed increased structural connectivity in white matter pathways, supporting the cross-wiring hypothesis (Dovern et al., 2015).

Impact on Perception and Creativity

For those with synesthesia, their unique sensory experiences can profoundly affect their perception of the world. Synesthetes often report enhanced memory and creativity. The vivid and consistent sensory associations can make abstract concepts more concrete, aiding in tasks like memorization and artistic creation.

Many famous artists, musicians, and writers are believed to have had synesthesia, including Vincent van Gogh, Wassily Kandinsky, and Vladimir Nabokov. Their synesthetic experiences may have contributed to their innovative and distinct styles. A 2018 study found that synesthetes are more likely to engage in creative activities and exhibit higher levels of creative thinking compared to non-synesthetes (Rothen & Meier, 2018).

Living with Synesthesia

While synesthesia is not considered a disorder, it can sometimes pose challenges. The constant influx of sensory information can be overwhelming, leading to difficulties in concentration or communication. However, most synesthetes embrace their unique perception as a part of their identity.

For example, a person with chromesthesia might find it challenging to focus in noisy environments but may also enjoy the added dimension of color in their musical experiences. Similarly, someone with lexical-gustatory synesthesia might have strong aversions or preferences for certain words due to the tastes they evoke.

Statistics and Data on Synesthesia

Recent studies provide valuable insights into the prevalence and diversity of synesthesia. According to a 2019 survey, approximately 7% of the population may experience some form of synesthesia, a higher estimate than previous reports (Simner et al., 2019). The same survey highlighted that grapheme-color synesthesia is the most common type, affecting about 1.4% of the population.

Recent studies provide valuable insights into the prevalence and diversity of synesthesia. According to a 2019 survey, approximately 7% of the population may experience some form of synesthesia, a higher estimate than previous reports (Simner et al., 2019). The same survey highlighted that grapheme-color synesthesia is the most common type, affecting about 1.4% of the population.

Additionally, research indicates that synesthesia is more common in women than men, with a ratio of about 3:1 (Barnett et al., 2008). This gender difference adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of the phenomenon.

Conclusion

Synesthesia offers a remarkable glimpse into the complexity and interconnectedness of the human brain. By studying this phenomenon, scientists can gain deeper insights into sensory processing, neural plasticity, and the nature of perception itself. For those who experience synesthesia, their world is enriched with an extraordinary tapestry of sensory connections, making their perception truly unique.

References

- Barnett, K. J., Finucane, C., Asher, J. E., Bargary, G., Corvin, A. P., Newell, F. N., & Mitchell, K. J. (2008). Familial patterns and the origins of individual differences in synaesthesia. Cognition, 106(2), 871-893. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.05.003

- Cytowic, R. E., & Eagleman, D. (2009). Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia. MIT Press.

- Dovern, A., Fink, G. R., Fromme, A. C., Wohlschläger, A. M., Weiss, P. H., & Riedl, V. (2015). Intrinsic network connectivity reflects consistency of synesthetic experiences. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(21), 7679-7687. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0320-15.2015

- Hubbard, E. M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2005). Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia. Neuron, 48(3), 509-520. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012

- Rothen, N., & Meier, B. (2018). Higher prevalence of synaesthesia in art students. Perception, 37(6), 828-831. doi:10.1068/p5875

- Simner, J., & Hubbard, E. M. (Eds.). (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Synesthesia. Oxford University Press.

- Simner, J., Carmichael, D. A., Hubbard, E. M., & Rotroff, S. (2019). A fundamental change in our understanding of synaesthesia: Prevalence, structure, and function. Cortex, 119, 197-205. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2019.04.010

- Ward, J. (2013). Synesthesia. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 49-75. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143840

- Witthoft, N., Winawer, J., & Eagleman, D. M. (2015). Prevalence of learned grapheme-color pairings in a large online sample of synesthetes. Consciousness and Cognition, 35, 156-165. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2015.02.012